Quantum

New Member

- Dec 20, 2025

- 4

- 10

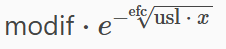

Problem: I've always liked the science point system in the KSP, but it has a number of shortcomings that I believe can be addressed.1. The first shortcoming was that instruments designed for long-term, productive operation, rather than for a one-time science yield, such as telescopes or magnetometers, quickly became unusable for science point yield. (Even now, the Voyagers are transmitting data, and this temperature and pressure data provides scientific value.)Proposed solution: I crunched the numbers a bit and may have found a formula that can flexibly adjust the amount of science yield and how long it will be effective.

where:

x - Time or number of measurements made by the instrument under specific conditions;

usl - observation futility modifier. The smaller it is, the more gradually the science points drop. This can depend on the combination of the instrument's characteristics and the usl modifier of the environment.

efc - the efficiency of the scientific instrument during operation; the higher it is, the longer the instrument will yield science.

modif - an environment modifier that indicates the value of science based on the environment it's in: (Location/planet, division into levels of extremity (normal/elevated/extreme, etc.).

The amount of science produced by the device's operation should be calculated as the sum of the science from each unique modifier.

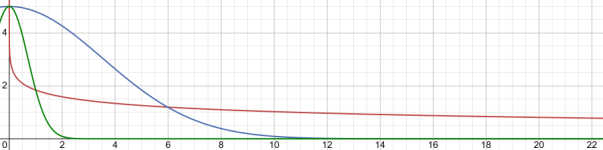

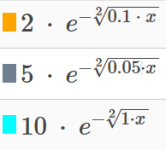

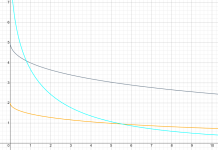

Here are a couple of examples regarding efficiency:

1.In the first case (red graph), let's imagine that we installed a barometer on the spacecraft, and it will continue to return data from orbit for a long time.

2.In the second case, it could be the result of some experiment in orbit. While it might yield scientific results several times, by the sixth dimension, it would only yield 20% of the original data, and by the tenth dimension, it would be almost zero.

3.And in the third case, it could be an experiment observing the environment from an astronaut. They might report something interesting the first time, but by the second dimension, this information would be useless.

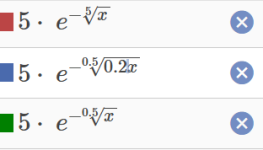

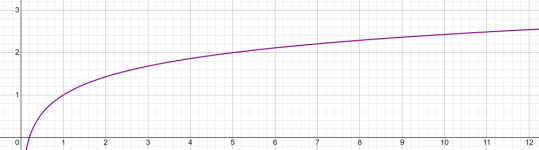

Examples of calculating science gain relative to environmental sets:Let's imagine how science gain should be calculated for one device when exposed to different environments. Each time a modifier appears that the device hasn't previously encountered, its countdown time starts at 0 (we can measure X in seconds, minutes, or hours).

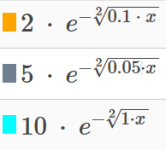

For example, we have a radiation meter. It operates with a uniform efficiency of 2.

1. Let the yellow graph be its base science gain over time, with a base modifier of 2 and a futility of 0.1.

2. We enter orbit (blue graph) and begin measuring radiation. The data there is certainly valuable (modifier 10), but its relevance (futility modifier) will quickly decline and soon be reduced to the usefulness of ordinary data, since in most of space this data will be available to us anyway.

3. And then, suddenly, on a flight to the moon, we detect a surge in radiation, and we fly through Van. Allen radiation belt (gray graph). The data is valuable, and due to its locality, it has a high relevance of 0.05, and we would have liked to linger and study it longer, but we flew through it for an hour, collected only a small portion of the science, 5 according to the schedule, and then flew on. However, if we had sent a spacecraft specifically there, it could have operated for 50 hours and collected a mountain of science before it failed.

And finally, we calculate how long the device operated under each specific condition, sum these values, and obtain the total science from the device for the flight.

Furthermore, taking the "definite integral" will allow us to determine the maximum science a player can obtain in a given time/number of measurements, which will allow us to calmly monitor the balance of science and prevent situations where a player could have already unlocked half the science in the game by flying to Minmus.

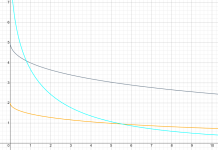

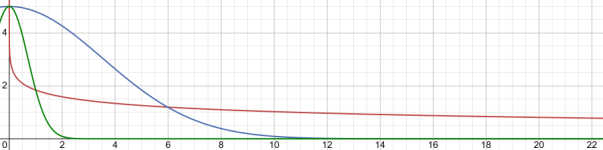

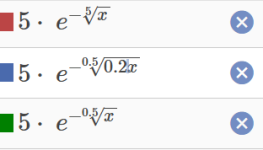

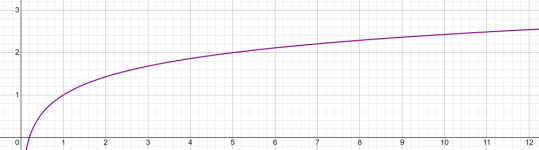

Also, an interesting idea is that if a player adds several devices of the same type, they can slightly increase the speed of obtaining that science (i.e., we'll increase X not by 1 over time, but by 1, 2, etc., depending on the number of measuring devices; the speed coefficient can be limited as a logarithm).

where:

x - is the number of devices

uls - is the uselessness coefficient (???); the higher it is, the smaller the speed increase from the number of devices.

So, with a "uselessness coefficient of 5," the speed of obtaining science doubles when using 5 devices:

2. The second problem, which many have noted, is the complete disconnect between measuring pressure or another scientific experiment and the subsequent acquisition of some engine for those points.

Solution: A long time ago, I saw a proposal to divide science points into fields: Engineering, Materials Science, Antenna Science, etc.I like this idea and, overall, it doesn't seem difficult to implement. The key feature of such a system would be that to obtain a specific science, you need to use parts that can be related to that science, and the conditions under which they were used (high pressure/temperature/radiation) could influence how much science we gain (see the formulas above). In this case, with each flight, we could earn some science simply by returning or transmitting telemetry about the condition of our parts.

I'll note that I'm not opposed to having a currency symbolizing "Fundamental Science" that can be converted into any research, but the amount of such science shouldn't be so widespread. Perhaps scientific instruments should provide precisely this kind of science, but in significantly smaller quantities or spread out over time, as opposed to actual testing of parts under extreme conditions.

I also absolutely support the idea of real useful data that a number of devices should provide: lidars, mapping, and weather data, but this has already been discussed in another topic, which I simply want to express my support for.

P.S. Guys, if you really like the concept, don't forget to vote, I'm worried that it might go unnoticed.

where:

x - Time or number of measurements made by the instrument under specific conditions;

usl - observation futility modifier. The smaller it is, the more gradually the science points drop. This can depend on the combination of the instrument's characteristics and the usl modifier of the environment.

efc - the efficiency of the scientific instrument during operation; the higher it is, the longer the instrument will yield science.

modif - an environment modifier that indicates the value of science based on the environment it's in: (Location/planet, division into levels of extremity (normal/elevated/extreme, etc.).

The amount of science produced by the device's operation should be calculated as the sum of the science from each unique modifier.

Here are a couple of examples regarding efficiency:

1.In the first case (red graph), let's imagine that we installed a barometer on the spacecraft, and it will continue to return data from orbit for a long time.

2.In the second case, it could be the result of some experiment in orbit. While it might yield scientific results several times, by the sixth dimension, it would only yield 20% of the original data, and by the tenth dimension, it would be almost zero.

3.And in the third case, it could be an experiment observing the environment from an astronaut. They might report something interesting the first time, but by the second dimension, this information would be useless.

Examples of calculating science gain relative to environmental sets:Let's imagine how science gain should be calculated for one device when exposed to different environments. Each time a modifier appears that the device hasn't previously encountered, its countdown time starts at 0 (we can measure X in seconds, minutes, or hours).

For example, we have a radiation meter. It operates with a uniform efficiency of 2.

1. Let the yellow graph be its base science gain over time, with a base modifier of 2 and a futility of 0.1.

2. We enter orbit (blue graph) and begin measuring radiation. The data there is certainly valuable (modifier 10), but its relevance (futility modifier) will quickly decline and soon be reduced to the usefulness of ordinary data, since in most of space this data will be available to us anyway.

3. And then, suddenly, on a flight to the moon, we detect a surge in radiation, and we fly through Van. Allen radiation belt (gray graph). The data is valuable, and due to its locality, it has a high relevance of 0.05, and we would have liked to linger and study it longer, but we flew through it for an hour, collected only a small portion of the science, 5 according to the schedule, and then flew on. However, if we had sent a spacecraft specifically there, it could have operated for 50 hours and collected a mountain of science before it failed.

And finally, we calculate how long the device operated under each specific condition, sum these values, and obtain the total science from the device for the flight.

Furthermore, taking the "definite integral" will allow us to determine the maximum science a player can obtain in a given time/number of measurements, which will allow us to calmly monitor the balance of science and prevent situations where a player could have already unlocked half the science in the game by flying to Minmus.

Also, an interesting idea is that if a player adds several devices of the same type, they can slightly increase the speed of obtaining that science (i.e., we'll increase X not by 1 over time, but by 1, 2, etc., depending on the number of measuring devices; the speed coefficient can be limited as a logarithm).

where:

x - is the number of devices

uls - is the uselessness coefficient (???); the higher it is, the smaller the speed increase from the number of devices.

So, with a "uselessness coefficient of 5," the speed of obtaining science doubles when using 5 devices:

2. The second problem, which many have noted, is the complete disconnect between measuring pressure or another scientific experiment and the subsequent acquisition of some engine for those points.

Solution: A long time ago, I saw a proposal to divide science points into fields: Engineering, Materials Science, Antenna Science, etc.I like this idea and, overall, it doesn't seem difficult to implement. The key feature of such a system would be that to obtain a specific science, you need to use parts that can be related to that science, and the conditions under which they were used (high pressure/temperature/radiation) could influence how much science we gain (see the formulas above). In this case, with each flight, we could earn some science simply by returning or transmitting telemetry about the condition of our parts.

I'll note that I'm not opposed to having a currency symbolizing "Fundamental Science" that can be converted into any research, but the amount of such science shouldn't be so widespread. Perhaps scientific instruments should provide precisely this kind of science, but in significantly smaller quantities or spread out over time, as opposed to actual testing of parts under extreme conditions.

I also absolutely support the idea of real useful data that a number of devices should provide: lidars, mapping, and weather data, but this has already been discussed in another topic, which I simply want to express my support for.

P.S. Guys, if you really like the concept, don't forget to vote, I'm worried that it might go unnoticed.

Last edited:

Upvote

3